[vc_row css_animation=”” row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern”][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Whose Streets? Power and Place in The Bahamas

BY CHANEL WILLIAMS

April 1, 2018

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space][vc_single_image image=”217″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” qode_css_animation=””][vc_empty_space][vc_column_text]Streets tell a story of economic, social and political power. This story of power unfolds when identifying who has access to streets, who owns property adjacent to streets, and who formally and informally regulates streets. Bay Street in Nassau, Bahamas, conveys a similar narrative. The artery where Parliament Square rests, this street welcomes millions of tourists each year and conveys the present and historical power dynamics of The Bahamas.

Streets tell a story of economic, social and political power.

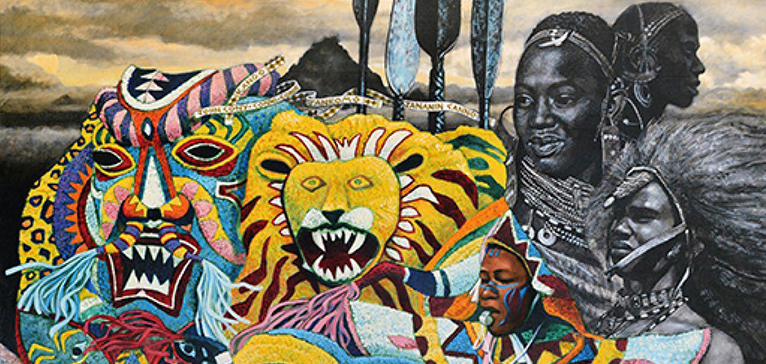

My earliest memory of Bay Street was when I was twelve years old. It was New Year’s Day and my mom, brother, and I decided to attend Junkanoo, an annual celebration on Bay Street. It was my first time attending the festival, and I remember seeing Junkanoo groups in intricate costumes playing Bahamian music. Bay Street was full of life and had made herself a welcoming host for the thousands of Bahamians who were ringing in the new year. No street can put on a show quite like Bay Street. Her narrow lanes create an intimate feeling that Nassau’s wider streets cannot. Her adjacent buildings, no taller than five stories, are ideal for capturing the sound of cow-bells and goatskin drums. Her history of power and protest lends itself to black bodies moving on asphalt in celebration.[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space][vc_single_image image=”218″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” qode_css_animation=””][vc_empty_space][vc_column_text]When slavery existed in The Bahamas, slave owners would give their slaves one day off work each year. On that day, usually around Christmas time, slaves would dress up in costumes and dance, or “rush,” down Bay Street. John Canoe, an African tribal chief brought to The Bahamas as a slave, led the demand for this celebration, hence the name Junkanoo (Sands, 2008). While Bay Street is often a space for festivities, events such as Black Tuesday uncover Bay Street’s palimpsest of struggle.

Tuesday, April 27, 1965, now known as Black Tuesday, was a historical moment in Bahamian history and the culminating critique and subversion of Bay Street’s existing power structures. During the 1960s, Bay Street’s stores and the Bahamian government were run by a white ruling elite. This control of Bay Street and the contentious political regime existed even though the demographic makeup of the country was majority black. Black Tuesday was a tipping point, a moment when politicians representing black communities could no longer stand by as gerrymandering policies marginalized their constituents’ voices. On Tuesday, April 27th, leaders and supporters of the Progressive Liberal Party marched on Bay Street in opposition to constituency boundaries that did not afford an equitable, majority black Bahamian parliament. Once they reached the front of Bay Street’s House of Parliament, protestors sat down, collectively blocking points of egress from the government building, and demanded equal political representation.

The Black Tuesday protests were not in vain, as it ushered in a new political era known as “Majority Rule”. The eradication of gerrymandering policies allowed the Progressive Liberal Party to win the 1967 election and to represent the needs of black Bahamians—needs that had long gone unheard and unmet. Six years after the Progressive Liberal Party garnered political power, The Bahamas gained independence from Great Britain in 1973, with Bahamians spilling into Bay Street to celebrate their newfound autonomy. These celebrations and expressions of freedom continue today and are found not only in Junkanoo, but also in the black-owned businesses located throughout the once solely white-owned Bay Street. This freedom is also found in children visiting the straw market after school, in Bahamian women perusing stores, and in black bodies moving through space without curfews or fears.[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space][vc_single_image image=”219″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” qode_css_animation=””][vc_empty_space][vc_column_text]Walking down Bay Street today, one might continue to ask who owns this street. The answer is not clear, nor should it be. Bay Street has always been a heavily contested space, and this conflict manifests in the monuments and buildings that frame her lanes. Busts honoring the men and women who helped the country gain independence are now juxtaposed with luxury stores like Diamond International. The ownership of Bay Street may be ambiguous and challenged in coming years, though Black Tuesday and the continued celebration of Junkanoo are reminders that black Bahamians will continue to have their place in Bay Street’s story.

When engaging with space such as Bay Street, planners should consider the histories of streets that we plan, as well as the subtle, and not so subtle, power dynamics of these corridors and the potential narratives that can unfold based on our planning decisions.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]