Diaspora Memory and the (Emotional) Infrastructure of Ex-Yugoslavia Collective Housing

BY NEVENA PILIPOVIC-WENGLER

May 21, 2020

Most academic definitions of infrastructure function under the influence of Western capitalist economic and technical norms. Even when such definitions focus on critiquing this influence, the arguments often reify the norms as the starting point, to which anything else functions as the alternative or the “other.” I have spent time amongst such an “other” infrastructure: the Yugoslavian collective housing complexes.

Before engaging with definitions of infrastructure, I already had a soft spot in my heart for the concrete apartment complexes of Belgrade (Beograd), Serbia, a former republic of ex-Yugoslavia. My mother grew up in New Belgrade (Novi Beograd) until her family immigrated to the U.S. to escape the dictatorship of Tito; I grew up hearing her paint the wonders of her childhood home on Blok Jedan (Block One).

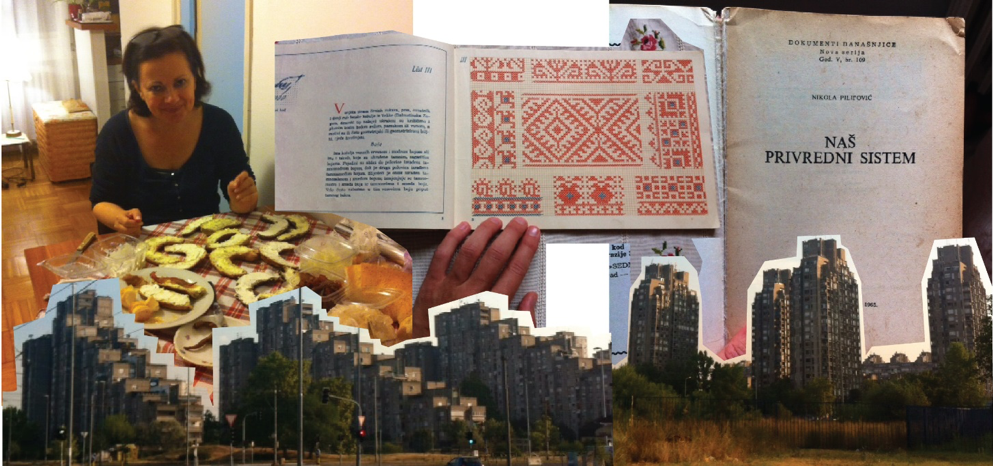

When I take photos of these buildings, I intend to capture the beauty I see in them, the fantastic geometrical design, a sense of awe. When I share these photos, I want to communicate that an incredible political project took place here, materializing in collective ways of living that (shocker) differ from the U.S.

However, I often fail in communicating such things. Friends and family not from Serbia often comment on how scary and dystopian the buildings look. One friend recently asked if the city is abandoned. I felt unnerved by the dissonance between my emotional reactions to these buildings and that of others. Am I blinded by Yugo-diaspora sentiment? Are my friends and family playing into anti-communist sentiment or phobias of public housing, predisposed to see these buildings as ugly?

When I step back and look at my photos, I empathize with my friends’ reactions. The three apartment complexes in the Banjica neighborhood of New Belgrade jet out from the ground and pierce the sky in an unsettling way. Despite the trees in the foreground, few trees, in fact, live directly next to these buildings. While I stood next to the middle one, a beer bottle cap fell to my left—someone living on one of those high floors using their window as a trash disposal. Or when looking at the interior of one of the collective housing complexes on Block 45—located on the Sava River, tucked between Block 71 and Block 44—the buildings crowd out the sunlight and could make one feel claustrophobic. But do you see that clothesline hanging across the abyss?

This clothesline embodies markedly different cultural norms from those of the American Suburbs I grew up in. In order to enter the clothesline’s concrete courtyard, one must walk through one of the many bypassing entrances that constitute the ground floor of the apartment buildings. This makes the buildings feel porous and interconnected. Hugged by humming bakeries, pharmacies, and salons, the ground floors feel alive. Families are also serviced by a variety of amenities within each “block” of New Belgrade, including schools, community centers, and markets.

The dense assortment of services and social spaces tells the story of the ex-Yugoslavian concept of “self-managing communities.” In this approach, hatched by the country’s socialist ideology, people lived right next to what they needed and could directly participate in the creation and maintenance of their lived spaces. When a new political system had guaranteed the right to housing in Yugoslavia’s constitution in 1950, the concept of self-managing communities materialized into housing infrastructure and permeated Yugoslavia’s architecture and planning ideologies.

In this way, New Belgrade’s housing served as an experimental site that sparked rich conversation between individualism and collectivism. It called on citizens to participate in their neighborhood’s design and planning as well as to use “self-management funds” for necessary developments. The national project of Yugoslavia espoused and implemented the self-managing framework, enmeshing the scales of country and neighborhood, tethered to financing, granting neighborhoods a significant measure of autonomy in giving shape to their communities.

Tamara Bjažić Klarin, an associate of the Institute of Art History in Zagreb, describes how these modes of architecture and planning “were attempts to reconcile the scale of socialist mass housing with that of consumerist individualism” (91). The buildings seem uniform at first glance—but look more closely and the apartments’ peculiarities and unique details reveal themselves. Try this with the photo of the Banjica apartment complex above—concrete gives way to energetic geometry which gives way to hand-painted signs, graffiti, and thriving plants.

I sense this in-betweenness acutely while staying with my mom’s childhood best friend, Sanja, on Block 45, where most of the photos were taken. I love to sit on her back deck, smelling the herbs growing in her concrete flower box. I look across a community playground at the neighboring apartments with the same concrete flower boxes, flourishing with greenery. The space feels alive, exhibiting each resident’s individuality while simultaneously conveying a visceral sense of collectivity. When Sanja and I take her dog, Aki, out for a walk on a warm autumn night, we encounter many generations using the same space—children running around, elders gossiping on a bench, young adults on dates strolling on the wide sidewalks connecting the Blocks. The dystopian concrete of ex-Yugoslavia—with increased privatization of this formerly collective housing and the current totalitarian government as its backdrop—quickly melts away into the present moment of a warm and interconnected space.

Perhaps my intimacy with the space explains why I think my photos capture vibrancy while my friends see scary cinder blocks. I am not external to this infrastructure; I spend coveted time with it each time I visit Sanja. I walk through it alongside others using it. In a piece on the infrastructure of intimacy, Ara Wilson, professor of gender studies at Duke, states that “infrastructure is a systemic assemblage of objects, codes, and procedures that, whether it fails or succeeds, is often an embedding environment for intimate life” (274). Can we flip that? To what extent does an emotional or intimate rendering of or attachment to an infrastructure re-assemble its objects or re-write its codes and procedures? I sense that our personal encounters, or lack thereof, with an infrastructure completely change how we read that infrastructure, if we read it at all. Does the infrastructure of national ideology depend upon this?

I grew up in a household that questioned U.S. white cultural norms because my mom grew up in ex-Yugoslavia and my Nikola, her dad, worked as an economic advisor for Tito and the socialist project itself. Does my intimacy with the emotional infrastructures of Yugo-nostalgia and Yugo-diaspora help me witness the promises this concrete collective housing made where many others only see failure?

I answer yes—I believe that my emotional infrastructures render visible the layers of intentional architecture and planning embedded within what otherwise might appear as unappetizing concrete.. I sense what’s possible as I bask in the buzz of Sanja’s Block 45. And I continue to learn of the previous generation’s imaginaries that were never fully realized. I reflect deeply on how architect Andrija Mutnjaković “tried to solve the housing crisis (as well as resolve the tension between individual initiative and collectivism) by proposing concepts in which a building’s structure and early construct would be financed from the public budget, while citizens themselves would carry out the rest of the building and participate in the final design” (Mrduljaš 50).

As Belgrade and the rest of Serbia increasingly transition from a socialist economy to a free market, this collective housing infrastructure is now subject to privatization and rent costs that are displacing residents. The global pressures of private capital—the majority of which is held by the few and is concentrated in capitalist economies, yet is extending its grasp into seemingly insulated spaces such as the blocks of New Belgrade—threatens to further drive a wedge between collective imagination and “economy,” the latter a naturalized facet of our capitalist, market society.

Capitalist economies flatten the definition of infrastructure to the machinations of “profit” and “private ownership.” Yet the ex-Yugoslavian visions (such as Mutnjakovic’s) and actualities (such as the built collective housing infrastructure) offer a vision of economics that orbit around collective decision-making with space for self-actualization and community. Connecting with my diasporic emotional infrastructure grants me access to this tangible imagination. As Ana Miljački puts it, “Reflective nostalgia is worth cultivating in the population of ex-Yugoslavians and their children… This new generation has the capacity to retool the project for the future” (11).

What can diasporic emotional infrastructures teach us in terms of becoming intimate with the infrastructures that we may not readily have access to in the countries, cities, or neighborhoods that we live in yet impact us every day? When we become intimate with these otherwise invisible infrastructures, we come to understand what exists and, thus, what we can change. What does your diasporic emotional infrastructure teach you?

References

Bjažić Klarin, T. (2018). Housing in Socialist Yugoslavia. In Stierli, M., Emerson, S., Kulić, V., Jeck, V., Bjažić Klarin, T., & Museum of Modern Art , host institution (Eds.), Toward a concrete utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980 (90-95). New York, N.Y.: The Museum of Modern Art.

Miljački, A. (2013). ONCE UPON A TIME: NOT EVERYTHING ALL AT ONCE. PRAXIS: Journal of Writing Building, (14), 5-6.

Mrduljaš, M. (2018). Architecture for a Self-Managing Socialism. In Stierli, M., Emerson, S., Kulić, V., Jeck, V., Bjažić Klarin, T., & Museum of Modern Art , host institution (Eds.), Toward a concrete utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980 (40-57). New York, N.Y.: The Museum of Modern Art.

Wilson, A. (2016). The Infrastructure of Intimacy. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 41(2), 247-280.