City of Barricades: Violent Eviction in Contemporary Rome

BY ELENA CLARKE

May 21, 2020

“When I first see you, I thought you should be scared.” It’s about midnight, and Fallou, a young man in his early twenties from Senegal, is walking me through Tiburtina Station to the bus stop. I’ve known him about a month at this point, during which time I’ve often stayed in Piazza Spadolini, located just outside the station, as late at 1am. After I inquire about his remark, he explains, “I do not like going to the city center. The people they treat me like I am dirty. They treat me like they are scared. If I want to talk, white women they run away.”

Fallou describes his hesitation in traveling to the city center, communicating the discomfort he feels as a result of being treated by Rome’s white residents and visitors with fear and disdain. He mentions, however, that he feels comfortable in one place: “Colosseum Park,” which is officially labeled Colle Oppio and is next door to the Colosseum. He likes to hang out there with African friends after showering at the Astalli Center, which is close by in Piazza Venezia. Large portions of the park have been under construction for over a decade, and temporary fences and construction materials are strewn all over the park. As a result, fewer tourists venture here compared to the way they swarm to most of the “historic” sites that surround it. Therefore, there are fewer police officers surveilling the area.

Public agencies have claimed it is necessary to maintain a more robust police presence in tourist areas for the sake of public order and for the security of Rome’s paying visitors. This results in racial profiling and the random search of young black men walking along the tourist streets of Rome. Unauthorized activities, such as selling unlicensed goods—which is often the only way that young men like Fallou can make a living while waiting more than a year for their documents to be renewed—risk the imposition of astronomical fines up to €7,000.

Stripped of the particularities of their identities, young men like Fallou have been labeled by the state as simply “African,” “black,” or “migrant.” Because of these labels and the prejudices that have been attached to them by white Europeans, each of these young men experiences visible and invisible barricades daily. This reproduces a pattern of psychological and physical displacement for them, shaping their perceptions of “no-go zones” in the city while limiting their quality of life in Rome. Marginal spaces in the city such as Colle Oppio and Piazza Spadolini become sites where young African men can comfortably express their individuality, in contrast to most sites in Rome where their identities are heavily policed.

I visit Colle Oppio at night with Hamadou, a young man from Mali, who is sleeping in the park after being evicted from a state-funded shelter. Administrators of the shelter, a secondary reception center for asylum-seekers in the Torre Maura neighborhood of Rome, evicted Hamadou and several others because they could not secure a legal work contract. He was given one week’s warning before being required to pack up his belongings and leave the center. Administrators made no attempts to re-house him or Moussa, another young Malian who was staying in the same shelter. At the time of his eviction, Hamadou had just finished a work training program for construction and demolition work. His employer, an Italian woman, was paying him ten Euros a day and refused to give him a legal work contract. His employer was likely assuming that Hamadou would be less likely than a European worker to demand fair wages and a declared contract. Because he was evicted, Hamadou had to quit even this exploitative work arrangement. Living in the park, he had no shower and no electricity, so he found it difficult to wake up and prepare himself for work.

The park is locked at night, so we climb a fence.

“Hama!” someone calls out to us from a group of three men in the distance. Hamadou turns to me to ask if we can approach. “They are Malian,” he says. “Those are my brothers. Anytime you see men huddled in a circle sharing food they are probably African.”

We walk over and I meet Moussa for the first time. He met Hamadou in Rome years earlier and had been the first to inform Hamadou that a group of Malian men were sleeping in Colle Oppio. The three men we join have disassembled cardboard boxes to create a rug at the foot of a tree. They are listening to music and using their backpacks as pillows to support their heads, speaking to each other in Bambara and to me in French. “The effects are getting to me,” Moussa tells me. “It’s been ten years that I can’t get a definitive answer on my documents. Ten years that I can’t access a stable job or a stable house.”Hamadou turns to me and says, “Come with me and I’ll show you my ghetto.” I ask why he uses that word and he tells me that “ghetto” is the word he used in Mali to describe a place with no running water, no central electricity, and no toilets. We climb through a broken part of a fence that serves as the barrier around one of the park’s construction sites, and he shows me where he has been living. He prefers sleeping here, though it is farther away from his friends, in order to avoid being woken up early in the morning by scattered groups of tourists. “I have a tent but I can’t use it,” he tells me, explaining that if police officers see a tent they will force him to take it down or they will confiscate it.

A week earlier, Hamadou had shown me his reception center, which is located in a former hospital surrounded by twenty-foot metal fencing. The shelter that he lived in is over an hour and a half of travel from Rome’s city center using public transportation.

When we arrived at the center, Hamadou explained that as a white woman, I should be required to sign in as a visitor. Black visitors, on the other hand, could enter the center “unnoticed” at night because the operators only bothered verifying the identities of black occupants in the morning – and only if there were more than the assigned number of guests in a single room. Official visitors were not allowed to see the conditions of the bedrooms and could only stay in the shelter’s common areas under supervision of the center’s administrators.

However, Hamadou explained that if we snuck in through the back I would not have to sign in and that I would be able to see the sleeping areas. Hamadou shared his small room with one other young man. Inside the room, there was a small sink, a wardrobe with a lock on it, and two twin beds with no sheets. The mattresses were chunks of yellow foam. As we left the room, Hamadou pointed to a black dot on the ground and said, “These are the things that bite. They make sleeping unbearable.” The black dot was a bed bug. Bed bugs, according to Hamadou, were the reason there were no sheets on the beds.

“Whites can’t come [to see the sleeping areas] because Italians think that they will tell other people about the conditions here,” Hamadou told me. “But we live here and we also have eyes and we also have heads. We can see that things are suspicious.”

As we left the room, I saw several men praying on small rugs in the hallways. The majority of the men staying in the center were Muslim from sections of East Africa, West Africa, North Africa, and Bangladesh. No prayer space had been designated for them inside the center, so they prayed in the halls, interrupted by people coming and going.

I did not meet Moussa at the center, though Hamadou pointed him out from far away when we were leaving. Moussa dragged his mattress outside into the courtyard because it was too hot inside to sleep without a fan or air conditioning.

Later that month, I found out that Moussa had been arrested after being searched “at random” in the tourist zone of Trastevere. At the time of his arrest, he had been living in Colle Oppio for three weeks; his arrest prompted a judge to order him “to leave Rome.”

One day while I am in Rome, Hamadou takes me to Rebibbia, a largely industrial area referred to by Italians as Tor Cervara. He wants to show me the Ex-Penicillina, a multi-story abandoned industrial complex that was once a penicillin factory. Large numbers of Africans and members of other excluded communities were living here until December 2018 when they were evicted by police. “This is the jungle,” he tells me, explaining that he heard Italians use “jungle” on the news. A French humanitarian worker who works with several local medical groups also uses this term when describing Rebibbia to me.

In a large concrete hall, small pieces of wood and cardboard that have been fixed together demarcate individual spaces of varying sizes, generally six to twelve square meters. “This is what I meant when I say my ghetto,” he tells me, standing inside one of the spaces. “If I lived here, in this nine-square-meter space that I built with these small pieces of wood, then these nine square meters would be my ghetto.” An Italian girl later tells me this is still the term used by Italians to signal neighborhoods where non-Italians live grouped together.

As we are leaving Rebibbia, Hamadou points out a shelter that is run by an Italian cooperative where he has played soccer before. The shelter is located inside a big white building removed from the road with a tall fence and barbed wire in front of it. It doesn’t look much different from the prison that is across the street.

A few blocks away from the Ex-Penicillina is via Vannina, where residents in another large industrial complex were evicted in 2017 and again in 2018. A young man named Adama, who I meet while he is volunteering for a local humanitarian medical group, tells me that he used to live there in his own “ghetto.” Despite having approved legal documents and a job with a legal contract, he couldn’t find secure housing. “People don’t want to rent to black Africans,” he tells me. “They think that if one comes then many will, but they forgot it was the same when Italians [emigrated] elsewhere.”

During the eviction of via Vannina, Adama tells me that the police entered the building early in the morning and started beating people in order to force them to leave. Adama lost sight in one of his eyes during this violent attack. The police proclaimed that they “couldn’t understand” what he was saying despite the fact that Adama speaks near-perfect Italian.

Adama continues to experience prejudice daily. He cleans hotel rooms and private apartment complexes for a living and has had the police called on him on several occasions. Many times, he explains, he will knock on the door of an apartment, and the resident or guest will refuse to open the door because he looks “suspicious” and “like he might steal something.” Doormen, which are common in Rome’s private apartment complexes, will sometimes chase after him when he enters the building even though he enters with the key given to him by his company. He explains with frustration that, when these kinds of things happen, his boss calls the client and apologizes to them, ignoring the effect on Adama. His boss carefully explains to the client that the cleaner is a black man. Afterwards, Adama is ordered to return and continue his work. If he refuses, he risks losing his job.

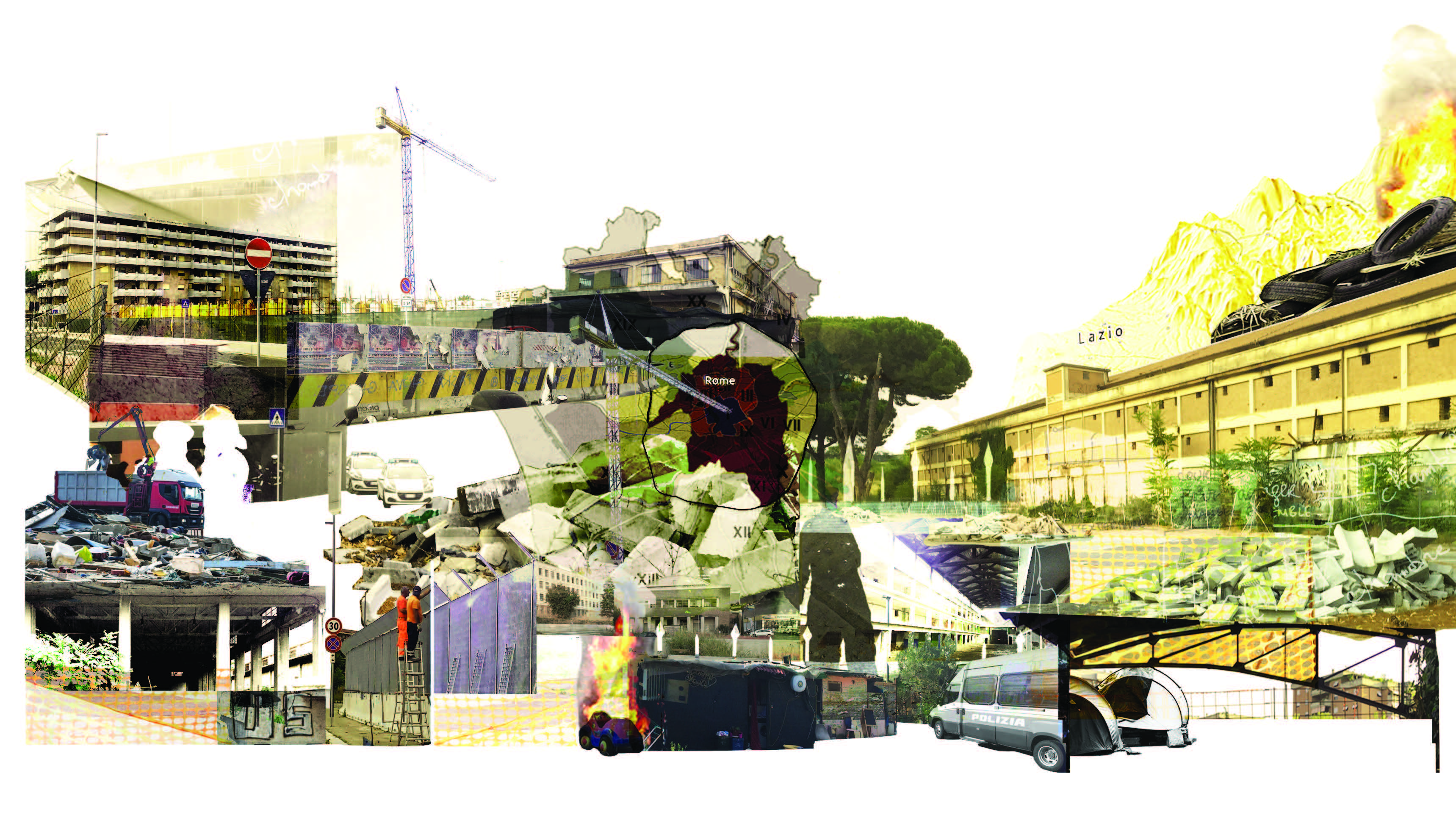

Today, via Vannina and the Ex-Penicillina are both surrounded by a mixture of concrete and metal barricades. The buildings stand empty and abandoned. Down the street, a building that was once the headquarters of an Italian magazine is still occupied by multi-cultural groups. Marked by the state for eviction in the near future, the occupants have constructed make-shift protective barriers by stacking empty metal bookshelves on top of existing fencing. I chat with a man who is standing guard at the front of the building. He explains that several similar occupations in the area are receiving protection from the Movimento di Lotta per la Casa, a collective of political groups in Rome that organize to protest eviction and to fight for housing rights.

I am already familiar with the Movimento. On July 15th, I joined them in protesting the eviction of the former school in via Cardinal Capranica, where mostly foreign-born families were living at the time. The eviction had been announced for seven o’clock in the morning, and the Movimento had planned “a human wall” to prevent police officers from entering and removing people against their will. National police forces, however, arrived at the school at 11 p.m. the night before in an effort to prevent people from organizing to block the entrance. In response, the Movimento and other supporters gathered in front of the barricade of police officers and protested for the remainder of the night while screaming into megaphones. In the morning, the protestors led an “unsanctioned” march in the neighborhood of Primavalle despite lacking a city license to protest.

On the other side of the police barriers, the residents built their own barricades with rubber tires and broken furniture that they lit on fire in an attempt to protect their homes. Some had lived in the former school for nineteen years.

After more than fourteen hours of stalemate, the residents surrendered. Families were relocated to the opposite side of Rome, not far from Torre Maura. Children had their school lives ruptured. In some cases, it was too late in the year to enroll in a new school. Single men were offered no alternative and simply made homeless. The state deployed over forty-five police vehicles including three fire trucks and a helicopter for the eviction of approximately two-hundred-and-fifty people.

I returned to the evicted building weeks later and saw that the police had sealed all the entryways and windows with concrete blocks. This, they hoped, would prevent residents from returning and would effectively prevent many from retrieving the belongings they had to abandon during the eviction. Other areas that were not sealed up were trashed and belongings were strewn everywhere. In some cases, rooms were even flooded – another police tactic to deter residents from returning.

These tactics, particularly sealing off entryways, are commonly deployed by police after evictions in Rome. Occupants of a house in via Fanfulla, where a group of approximately twenty people from Senegal lived together for years and had been paying rent, received an eviction order because the owner of the house sold the property. After being forced to leave, the group re-entered the building. They were evicted again after a few months of occupation and one week after the eviction at via Cardinal Capranica. This time, police officers sealed all the windows and doors with hollow bricks and mortar.

I visit via Fanfulla with Ibou, who at one point lived there. He explains to me how it had once been a site where he felt comfortable expressing his identity. “This was Senegal,” he tells me. “We could cook together. We could eat together. There is an outside courtyard where we could have celebrations.” Since we can no longer enter the building, he sketches the layout for me. Afterwards, Ibou, who loves to cook, takes me to a Senegalese restaurant around the corner, located in a family’s living room. “Along these streets, in apartments, there are many Senegalese living together,” he tells me.

Ibou has been living outside for several years when I meet him. He has lost or broken his phone many times recently, but he tells me that, in this neighborhood, “My friends, I will see them in the street, we will just run into each other. Sometimes I cannot contact them for years, but always on these streets I can find them.”

One day, I go shopping for spices with Ibou in what he refers to as the “Vittorio Emanuele” market, which is formally named Esquilino Market. The market is a collection of two buildings containing stalls near Termini Station. The area around the market, where nearly all of the local mosques are located, is a spot where many Sub-Saharan African men hang out.

It is also an area that is heavily policed. Outside the two market buildings, men commonly gather to sell unlicensed goods like phone chargers and bracelets. Several times a day—sometimes upwards of five—a vehicle belonging to one of Italy’s public policing agencies will drive through the pedestrian street in order to frighten the men away. Other times, Carabinieri officers enter the market buildings on foot from several entry points in order to surprise men selling unlicensed goods and ticket them. Fines for unlicensed selling can be as much as 7,000 Euros. In order to have legal documents renewed in Italy, all fines have to be paid.

Unannounced police raids are also common in Piazza Spadolini, where I first met each of these five men. The police drive by frequently, staring down occupants of the public square in what I imagine is an intimidation tactic. Sometimes, police officers arrive at five o’clock in the morning, searching the men’s belongings and asking them to produce documentation. Ibou tells me that after one of these searches, one of his friends disappeared. “I was scared and so I ran,” he tells me, describing the morning he woke up to police vehicles in the square. “My biggest regret,” he tells me, “is not waking my friend up and telling him to run with me. I never saw him again.”

Two days after I leave Rome, the police come to Piazza Spadolini unannounced and wake up the men sleeping there. One of the men sends me photographs of the police officers and their vehicles. They have rounded up the piazza’s occupants, searching the men’s persons and their belongings. The violent cycle of eviction in Rome continues.

Though the experience of barricades informs his daily experience in Rome, Fallou dreams of a better and more inclusive city. One evening in Piazza Spadolini he tells me, “If I had paper, I could draw you a city. I’m always just thinking of it in my head. It’s a place with a house for all of the people.” I tell him I have paper, and he quickly sketches a city plan, explaining to me that it has roundabouts so that cars cannot drive too fast and community gardens to foster sharing between inhabitants. It looks remarkably like the Garden City, a mid-century utopian urban project that privileged green space and developed in response to pollution and industrialization. “Alright, that’s cool,” he says when I google an image of the Garden City on my phone, “but I never seen it before.” As he reminds me, Fallou has never had a formal education.

Over the course of the next two months, I bring Fallou large pads of thick paper, rulers, and pens. In a nearby cafe, we digitize some of his sketches on my laptop and extrude them in 3D. He enjoys the precision of the computer, and I suggest to Fallou that he might go to school for city planning like I did. “That opportunity,” he tells me, “it is not for me. I don’t have the foundation. No, that opportunity, it is not for me.” A few weeks after I return to Boston he calls me and explains that he lost the ruler, the pens stopped working, and the paper is dirty. “It’s too difficult,” he explains, to keep drawing while living in the streets.