To Build A Lego House

BY JEREMY PI

April 12, 2018

In February 2017, The Guardian ran a peculiar article in its Technology section titled, rather provocatively, ‘Scraping by on six figures?’ Quoted in the article are several anonymous workers employed by various Silicon Valley technology companies, including Twitter, Apple, and Facebook, all describing their struggle to support families on annual salaries ranging from $100,000 to $1 million. At the heart of their woes are issues of housing affordability and availability–put simply, these top 1% of earners report themselves barely scraping by amidst a housing market unprecedented in its financial and social impacts.

The response to this article’s publication was mixed at best and extraordinarily polarizing at worst. As a public sector worker based in San Francisco at the time, I had friends and peers on both ends of the spectrum. Engineers and other tech workers were sympathetic, pointing to recent surges in both the rental and housing market as universally burdensome, regardless of individual income. Simultaneously, the remainder of Bay Area residents not employed by tech seemed to collectively scoff at the notion that these incredibly well educated and compensated workers were turning to news outlets to air their grievances regarding affordability.

Irrespective of the popular discourse, however, this article shed light on what has been a growing concern for all residents, businesses, and local governments alike: the need to address the issue of housing in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Bay Area Housing: A snapshot

Regardless of profession or socioeconomic status, the housing market in the Bay Area has developed at astronomical rates in the past decade. Amidst a perpetually growing population, the Bay has experienced a cacophony of new development and challenges with regards to providing living spaces for legions of workers, families, students, and long-standing residents.

Consider San Francisco as a case study. Rent has grown by 50% since 2010, while home prices have increased by 98%. Moreover, a report published in the same month as The Guardian’s aforementioned piece found that the city of San Francisco had some of the highest average rent in the entire world, estimating that a base income of $160,000 was needed to rent space for a family of four.

The figures only tell a portion of the story. Frequently left out of these reports is the impact that trends in the housing market has had on other aspects of living. Those who cannot afford to live in the immediate vicinity of their work have had to move and deal with longer commutes, exacerbating local traffic and parking scarcity. Older residents have also been priced out of previous neighborhoods and effectively forced to relocate, typically further away from vital health care facilities, walkable amenities, and social and community networks.

Those who cannot afford to live within the immediate vicinity of their work have had to move and deal with longer commutes, exacerbating local traffic and parking scarcity.

Perhaps most significantly, however, the underlying tension between the technology community and other residents has gradually created a perverse “us-versus-them” mentality. Deepening division has manifested itself in arguments played out in the media, everyday conversations, and internet forums, where topics of NIMBY-ism and class warfare are blatantly on display.

What then is to be done to address these crises? Enter Google.

Google, 2017

Since its inception, Google has called the Bay Area home. Founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page both attended Stanford University and gradually built their company out of garages and smaller offices dotted throughout Silicon Valley. The company eventually moved into its current headquarters in Mountain View in 2004, and since then has steadily expanded its campus footprint through land acquisition and consolidation. As of 2017, Google maintains offices in four of Silicon Valley’s most prominent cities.

As its campus and commercial activities have grown, so has its workforce. Google has long held a sterling reputation amongst the technology community and unquestionably attracts some of the most talented professionals in the world. Google’s headquarters alone is home to more than 15,000 workers, and with an upcoming opening of a new office in San Jose, the company is slated to welcome thousands of new employees in the next several years. The workforce is also a diverse community. In 2007, immigrants composed 8% of Google’s employees, with workers coming from 80 different countries. Furthermore, it is estimated that 37% of all tech workers in Silicon Valley are non-US citizens who entered the country on a company-sponsored visa.

Every worker, whether local or foreign, faces an arduous transition in moving to and living in the Bay Area. Individuals and families alike have gone to significant lengths to alleviate the burden of rent: some young, largely mobile professionals have resorted to living in crowded conditions with half a dozen individuals sharing a couple rooms. Families who are not nearly as flexible must move further away where rent is cheaper, but consequently face tedious commutes. In light of the living costs unique to Silicon Valley, Google is even now faced with a drain of talent as workers are opting to move into other cities that are not nearly as expensive and where even lower base salaries do not deny them a comfortable standard of living.

In light of an externally torrid housing market, Google has begun venturing into the realm of private, company-provided housing. The progress so far has been tenuous. Despite the technology giant’s notable economic impacts, dialogue between city departments and Google have not always been congenial nor collaborative. Merely a year ago in 2016, the City of Mountain View terminated a petition by Google to allow for the building of multi-story apartment buildings along a major boulevard adjacent to their main campus. This trend has continued as recent negotiations for an estimated 10,000 new living units on the condition of additional office space has stalled, with Google flexing its economic leverage and City board members refusing to budge.

Despite the technology giant’s notable economic impacts, dialogue between city departments and Google have not always been congenial nor collaborative.

Google Prefab

Amidst the shaky back and forth negotiations, it was reported in June that Google has put in an order for 300 prefabricated apartment units. A first-time construction firm, Factory OS, has been awarded the estimated $30 million bid and is slated to begin manufacturing the necessary pieces later this calendar year.

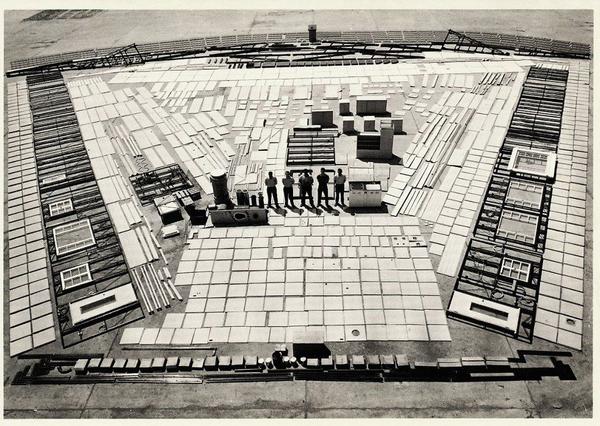

Prefabricated construction, also known as modular housing, is a method where individual components are manufactured off-site, and construction is simply a process of putting the pieces together to assemble a completed whole. Akin to LEGOs, prefab housing is marketed as an efficient and effective construction approach where contractors can compile components without the need for prolonged construction periods.

Factory OS boasts all manner of benefits to prefabrication: cost reductions; the ability to continue work despite poor weather conditions; better organization of materials and construction methods; greater efficiency and faster timetables. From their perspective, prefab units are here to revolutionize an otherwise stagnant construction industry that they claim is mired in traditional and ineffective methods. Innovation; efficiency; cutting edge: all characteristics that Google would use to describe their own business practices, and the pair appear primed to make their mark on the housing market.

Beyond the gloss of the advertisements, however, we see a conscious and calculated effort by a private company to provide a need for its workers. Despite Google’s multifaceted business ventures into machine learning, autonomous vehicles, satellite imagery, or advertisement and search engine capabilities, in this partnership with Factory OS Google as a parent company is now investing significantly in the private housing market in order to provide for a workforce that is vocal about its struggles.

Although the reports do not provide all the details, I hypothesize that these ‘temporary’ units will be offered to new employees either moving across states or countries. Especially for newly-arrived immigrants, I posit that Google plans to provide these prefabricated units as temporary accommodations that would allow for immediate move-in, thereby giving residents a period of time to establish roots and look for more permanent housing, without the immediate urgency.

The initial order of 300 units constitutes a literal drop in the bucket relative to the anticipated 20,000 new employees Google plans to hire in the coming years, but it is a quantifiable start. Given time, and based on the success of this first wave, it would be reasonable to expect Google to expand their operations, given the company’s considerable resources.

Interlude

In considering Google’s latest venture into prefabricated housing, I was struck by the parallelism with an earlier attempt to promote prefab as a means for addressing a dire housing crisis. Google and Factory OS are not the first to promote prefabricated construction – the technique is several hundred years old and can be traced back to the Industrial Revolution. In Lustron Corporation, we similarly observe a unique situation where prefab units were, for a moment, considered the saving grace for escalating demand for affordable housing in the post-World War II period. Backed by the Federal Government rather than a corporate entity, Lustron Corporation was ultimately a doomed venture that would squander three quarters of a billion dollars and close its doors after just five years.

In considering Google’s latest venture into prefabricated housing, I was struck by the parallelism with an earlier attempt to promote prefab as a means for addressing a dire housing crisis.

Lustron Corporation, 1947

Post-World War II America was not altogether different from contemporary times when viewed from the perspective of housing. Thousands of returning veterans came back to a country marked by housing shortages and exorbitant housing prices. Statistics show that 3 million homes were needed between 1946 and 1947 to meet immediate demand, and 12 million more over the coming decade. Furthermore, an estimate from the time also found that the cheapest home was whole unaffordable for 79% of American families. GIs flush with wartime earnings were willing to spend, but simply had nothing they could purchase.

In the war’s immediate aftermath, the private housing market was largely ill-prepared and incapable of providing housing at the required volume. Demilitarization of manufacturing facilities and raw materials was a bureaucratic process that was going to take time, yet the urgent need for cheap, durable, and widely available housing could not be ignored. An innovative approach to housing production was deemed necessary, and in a perfect storm of events Congress passed the Veterans Emergency Housing Act, which granted surplus war plants and resources specifically to construction firms. In addition, Congress created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) which promised federally-backed loans to those firms deemed most worthy and capable of delivery. Lustron rose to the top, and in 1946 found itself with a $12.5 million loan (approximately $170 million in today’s money) intended for 15,000 new units.

Lustron Corporation distinguished itself from the then saturated market of postwar construction companies through its ability to publicize, and the scope of its aspirations. Even before its first home had been completed, the company had already embarked on a nation-wide campaign to generate interest. Hundreds of dealerships sprung up and orders came flooding in, and the company benefited handsomely from positive press, complete financial support from the federal government, and even constructive dialogue with local labor unions.

Lustron’s founder, Carl Strandlund, had even grander visions for his product beyond satisfying the immediate housing demands. Akin to Factory OS’s discourse, Strandlund was also inspired to inject innovation, greater efficiency, and rationality into the construction industry by incorporating mass production techniques. Lustron houses were designed to perform exactly as their contemporary counterparts: individual components were massed produced at a factory, then delivered directly to the building site. Prefabrication techniques were intended to drive down both the cost of production and purchase, with each crafted unit featuring built-in amenities and appliances that also spoke to the modernity and innovation philosophy inherent in their design methodology.

Downfall

Then everything came crashing down almost as quickly as things were built up. Despite everything working in Lustron’s favor – the financial, physical, and technological resources that allowed for work on a scale that had previously been unimaginable for a private housing contractor – the company declared bankruptcy less than three years after they had been widely championed as the solution to the housing crisis.

Reasons for the company’s demise are numerous. From a production perspective, Lustron was never able to attain an optimal rhythm in its manufacturing. Prefabrication requires highly specialized infrastructure to enable its mass production capabilities, and Lustron was plagued by issues with its equipment that resulted in a sluggish pace and sparse output relative to its ambitions. Combined with external factors such as shortages in materials and delays in delivery, the first homes took two years construct and were anything but the promised timely and efficient alternative to traditional home building methods.

Lustron also faced large structural issues in the realm of finance. Overreliance on the local dealership model and the swathe of hidden cost burdens eventually forged a tenuous relationship with distributors, an issue exacerbated by the fact that Lustron simply could not deliver the houses in a timely and consistent manner. Broader financial institutions were also confounded with approaching a new housing typology in prefabricated units, and conservative banks were largely unwilling to grant mortgages to would-be purchasers for what banks classified as nontraditional homes.

Perhaps most damning was the continued support of the federally-backed RFC throughout the entire production cycle. Despite incessant delays and a gradual decline in popular perception towards Lustron’s efforts, the government continued its lending practices and funded the project to the bitter end. Although political pressure and accusations of favoritism did eventually force the RFC’s hand in 1950 to recall the entirety of Lustron’s loan, $52 million ($731 million in 2017) had already been sunk into the project that had delivered less than 3,000 units over a two-year span: a far cry from the promised 30,000 homes each year.

Convergence

Lustron’s fate is not Google’s inevitability. Although any comparison begs many uncertainties and questions, I believe the story of Lustron Corporation offers some fascinating insights and wrinkles when contextualizing it with Google’s efforts in 2017 to promote prefabricated housing as a potential solution for its workers.

One of the primary issues with Lustron’s development can be attributed to its financial benefactor being unwilling to walk away from the partnership until that decision was forced upon them. Douglass Kerr even makes the argument in Suburban Steel that Lustron would have succeeded had it not been for federal creditors cutting them off and forcing a foreclosure. While Google has already invested $30 million into their venture with Factory OS, I believe that Google will be well served by its track record of being unafraid to shut down heavily-invested ventures should they prove to be unsuccessful. Google Glass, Buzz, and countless software projects have all been quietly shelved in years past despite millions in development. Reevaluating the effectiveness of these first 300 units will be key.

On the manufacturing side, Lustron’s operations did little to reinvent the prefabrication wheel, and Factory OS will need to be cautious in their approach to mass production. The contemporary facilities appear to be adequate, but one of Lustron’s biggest detractors was the complexity and rigidity of its design, where the components Lustron produced could only function with other Lustron-produced pieces. Factory OS is similarly dealing with their very first project as a firm, and it would behoove them to use industry-wide standards in their manufacturing.

Most importantly however, Google will need to be intentional and cautious about how these projects are marketed, discussed, and understood within the common discourse. In the earliest stages of operations, Lustron benefited immensely from a successful PR campaign that helped drive support and interest for the project. Through the power of advertisement and positive press, the corporation was able to champion their methods as the ultimate solution to housing and affordability.

Lustron’s fate is not Google’s inevitability.

Conclusion

As with any project that runs against the grain of common practice, Factory OS and Google face a steady climb as they work towards implementation of their plans. The early media attention has been thus far understated, as the respective negotiations and developments remain shrouded behind speculation, confidentiality, and a collective uncertainty. Whether modular homes or company-sponsored housing developments will signal a dramatic shift in construction practices or corporate portfolios is difficult to predict. Speculating the impacts of the project on broader trends in affordability, displacement, and accessibility are likely premature, but inevitable given the recency of public outcry and political tension toward’s Google’s development efforts.

In her book Building the Dream, Gwendolyn Wright describes Lustron as existing in a moment in time characterized by ‘recurring government belief in dramatic technological solutions for complex housing problems.’ (244) Prefabricated housing was but a necessary evolution for the construction industry – or so it was thought. Wright posits later, that ‘People expected too much too soon from innovative technologies’ (245). Especially with a company name that carries such gravitas, Google I believe is being wary about this latest venture into worker housing. Although it’s doubtful that they have Lustron in their collective conscious, the current social climate warrants a sensitive, mindful, and perhaps conservative approach to the introduction of Google’s LEGO homes.

References

Baron, Ethan. ‘Mountain View slashes planned Google-area housing.’ The Mercury News. June 23, 2017.

Broache, Anne. ‘Google: Foreign workers are key to our success.’ CNet. June 6, 2007. Castillo, Michelle. ‘San Francisco has gotten so expensive, some tech companies can’t convince employees to move there.’ CNBC. April 6, 2017.

DeBolt, Daniel. ‘Google housing axed in city’s general plan.’ Mountain View Voice. July 13, 2012.

DeBolt, Daniel. ‘Google pressures city over N. Bayshore plan.’ Mountain View Voice. February 17, 2010.

Dineen, J.K. ‘Vallejo firm bets on modular housing to meet critical shortage.’ San Francisco Chronicle. October 18, 2017.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier. Oxford University Press. 1985.

Knerr, Douglass. Suburban Steel: the Magnificent Failure of the Lustron Corporation, 1945 – 1951. Ohio State University Press. 2004.

Kusisto, Laura. ‘Google Will Buy Modular Homes to Address Housing Crunch.’ The Wall Street Journal. June 14, 2017.

Mitchell, Robert A. ‘What Ever Happened to Lustron Homes?’ The Journal of Preservation Technology. Vol. 23, No. 2. 1991.

Salon, Olivia. ‘Scraping by on six figures? Tech workers feel poor in Silicon Valley’s wealth bubble.’ The Guardian. February 27, 2017.

Wallace, Nick. ‘What is the True Cost of Living in San Francisco?’ SmartAsset. June 7, 2017.

Wolfe, Tom and Leonard Garfield. ‘A New Standard for Living: The Lustron House, 19461950.’ Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture. Vol. 3. 1989.

Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream. MIT Press. 1983.

‘Majority of Silicon Valley employees are foreign born: Report.’ Gadgets Now. February 13, 2016.

Photographs

Hand-eye Supply. ‘Lustron, The Alle Steel House.’ September 4, 2015.

Danaparamita, Aria. ‘Lustrons: Building an American Dream House.’ National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Factory OS. ‘Our Story’