Ecology of Uncertainty: A Spatial Meditation on Emptiness

BY YESENIA PEREZ & YENI YI

June 28, 2021

1

1

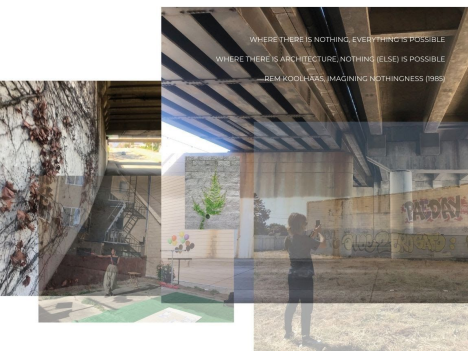

What grows beneath a freeway? Mildew, moss, mold, lichen and fungi. Creeping vines and invasive species. Spontaneous subterranean vegetal life emerges from total communion with an environment marked by highway traffic induced vibrations, pollution, and relative lack of sunshine.2

What lives beneath a freeway? Here, at the underpass, debris and dust has collected. Discarded masks, antibacterial wipes, and needles are carried through the city on natural currents and deposited at the vertex.

Sickness lives here. The waste generated by a multiplicity of pandemics coalesce under this freeway.

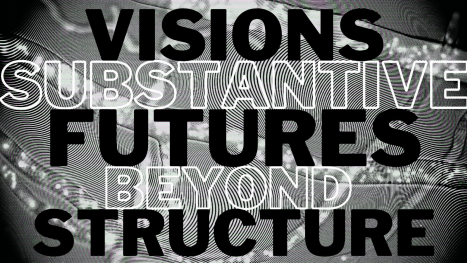

Perhaps, the real question is not what grows or lives beneath a freeway but, instead, what grows from uncertainty and lives in emptiness?

Our meditation is entangled in spaces of least surveillance dismissed as unsanitary, marked by sickness; the byproduct of the materiality of California freeways: the underpass as charged emptiness where mutations of unregulated movement patterns represent the possibilities for a liberated future and self-determination; underpasses as an invigorating site of transgression, struggle, and refusal against supremacy3 that at its genesis was simply planned as a point of intermediary transit but evolved into a living home, a dynamic incubator, and a vehicle for inter/cross-species exchange. The embodiment of dialectical between representations of space and representational space.4 The underpass in all of its emptiness is not nothingness as nothingness is traditionally defined by absence, but rather a nothingness composed of thick presence.5 And, if breath is presence6 and presence is abolition,7 then we find ourselves directly speaking to the urgent and necessary processes of creating life-affirming conditions, through breathing in the emptiness.

Let us breathe, together, for a moment. Even when it is dangerous.8 And ask of each other, what can unbecoming look like? How do we ourselves unbecome? We ambitiously set forth to complicate pathologizing white supremacist ideologies of sickness, use value, and production under late stage capitalism imposed over the blankness9 of public space. And ask of each other, what are the conditions for freedom? Our provocation: emptiness. Let us wander, together, for a moment into the sickness and the uncertainty of the void, entering into communication with nature, with the other(s), and with ourselves more fully for the purposes of cultivating a collective dream—an imagination—for our freedom.10

11

11

The American fanaticism around hygiene, correlating purity with health and dirt with sickness, was historically constructed to deem spaces uninhabitable and people unworthy.12 The exclusion of ‘dirt,’ interchangeable with the exclusion of ‘dirty people,’ is conflated with an aversion of the foreign to drive an “ethical ‘sickness’ of hierarchical exclusion.”13 Internalizing these practices has sowed an irrational fear of dirt and distanced us from intuitively engaging with and navigating through our surroundings. Cultural hegemony flattens out the dissonance between obsessive hygienic practices and our relationship with the earth, “[pitting] us against our microscopic surroundings.”14

The ultimate form of oppression is epistemic extraction—that which gouges from our bodies the memories and sensations of our homes. What remains is sterile, dull, fearful, unquestioning. Perfect husks.

What are the implications of losing our connection with the spaces we inhabit? Further, what are the implications for the means of connection increasingly to be through a divide? How does it affect our ability to be more human, humans?15

16

16

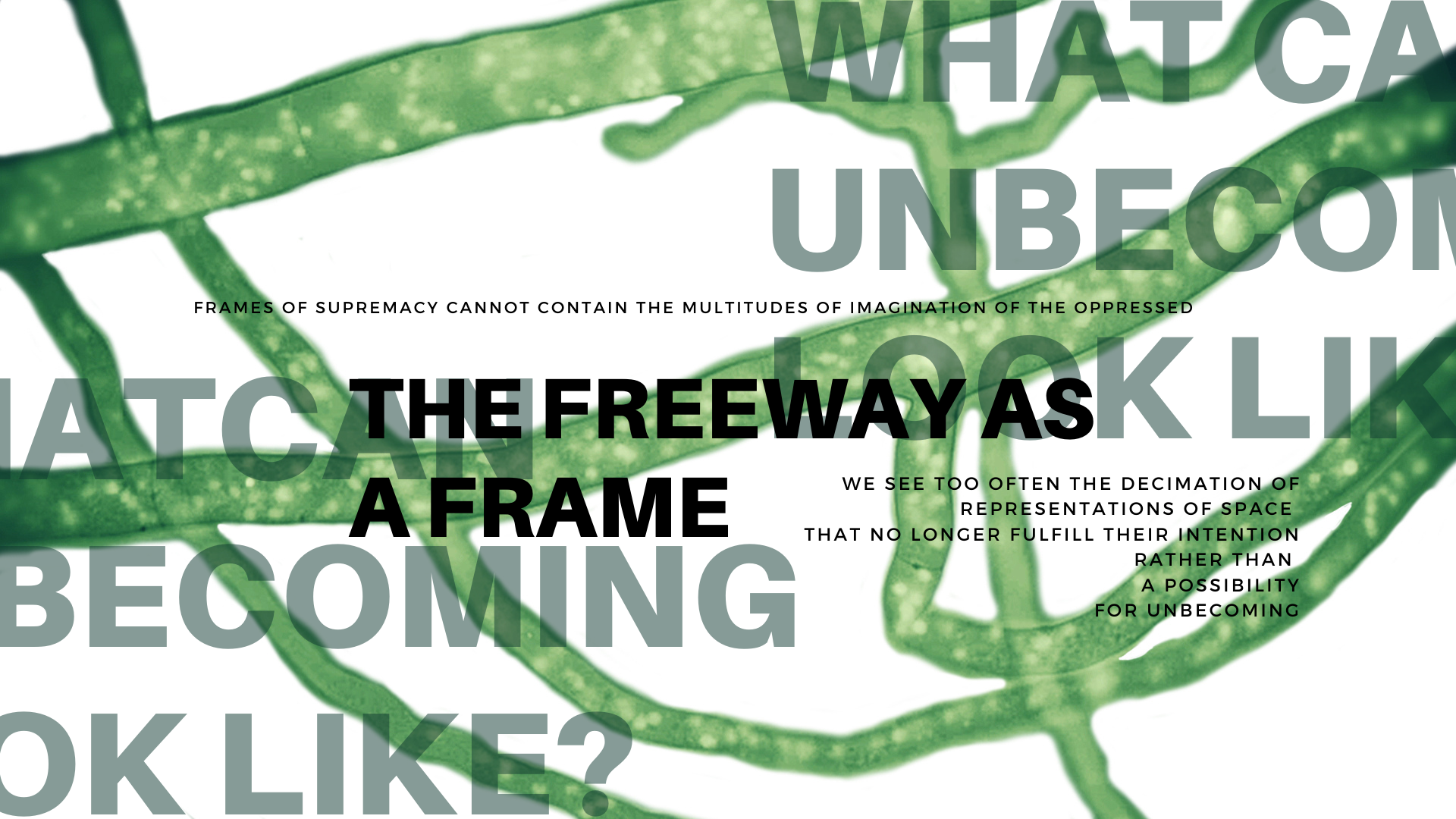

Bernard Cache proposes that the built environment is a series of frames designed and deployed by the architect that can exist in stasis independent of classical causal scheme. This desire for the city and its elements to continue in perpetuity untouched functions to 1) render the city an abiotic object and 2) inherently demonizes decay consequently positioning the process, unnecessarily and illogically, opposite of (re)generation—in other words: life, birth, creation.

Voids are seen as teeming with possibilities. The immediate compulsion is to colonize, to fill these voids with intentions and material things to bring order to the unknown, to invalidate what already exists. Capitalist logic renders a space useless when it no longer produces, and that which is useless is dead. Regulations are created in an attempt to control what flows between each methodologically planned component, and the surveilled move cautiously. The watchers observe and modify the social and physical constructs necessary to maintain such order. They fear the spontaneous. They fear life.

Life is what charges the space in between physical forms, an unpredictable “intercalate phenomenon” that moves through probabilistic frames.17 The gap between the frame and the designer is not the time that passes, but rather what phenomena charges the space.

All frames are representational. All frames can unbecome.

What if our bodies were the conduit to transmit that charge or phenomena? We collectively have the power to transform a representation of space.18 All that is unproductive must be bleached and stripped away, and all power that cannot be controlled must be extracted. We see this fear of life in the sterilization of our spaces and our relationships to them. What else in our bodies have we forgotten, and why were we made to forget? Audre Lorde asserts in her essay “Uses of the Erotic: the Erotic as Power”: for the erotic is not a question only of what we do; it is a question of how acutely and fully we can feel in the doing. Perhaps, in the undoing: the dreaming.

19

19

Minimalist sculpture artist Carl Andre problematized that a thing is a hole in a thing it is not. The space beneath a freeway is excess waste that exists outside of the frame of built structure: the highway. It is by consequence supportive but not sovereign; existing only in so far as the freeway stands. Most of all, it is nothing. Unpredictable and open space ripe for uninhibited activation masked by misappropriated associations to dirt, sickness, and decomposition—a living threat to carceral logics of sanitation, structure, punishment, order, and extraction.

What grows from uncertainty and lives in emptiness? Freedom.

Public spaces that are both symbolic and material sites of freedom reject iconography by allowing for their own subversion.20 The very nature of the underpass as unsurveiled, (s)porous and permeable make it fertile ground for un-oppressed play and organic emergence. Play as both pleasure and ontology sensemaking. Which leads us to ponder, can we intentionally create conditions for nothingness that reject the neoliberal (re)commodification of emptiness under white supremacy?

How might we fix ourselves temporarily in a space that is always changing, and by consequence, changing us in equal measure? At the root of our meditation, we recognize that colonization is as much psychological as it is material. It serves the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy to convince people their dreams, both in sleep and while waking, are fundamentally not real21; they are trivial, inconsequential, and fantastical illusions that at best are certainly not to be taken seriously. They are immaterial after all. We can only hold a dream the same way we hold emptiness. But here, in the emptiness, we recognize dreams incubated in and articulated through public space as the landscape for a type of intimacy without proximity across temporalities; not a “virtual” presence but a “real” presence caught up in loopy materialities.22

Meaning, you and I and we find ourselves miles, continents, time zones, and even years apart untangling threads of dreams like tendrils of the vines that crawl along the concrete pillars of an underpass. Here at the underpass the microscopic, nearly undetectable elements of our breath pass between us as effortlessly as dreams should. Not the promise of a destination but the invitation to be present with the parts of ourselves that intuitively question each and every oppressive frame, ideology, and materiality that shape public space and our lived realities. Rather than seeing utopias as blueprints, Duncombe (2017) sees utopias as provocations: “by asking ‘What if?’ we can simultaneously criticize and imagine, imagine and criticize, and thereby begin to escape the binary politics of impotent critique on the one hand and closed imagination on the other.”23

A multiplicity of imaginations coalesce in the emptiness.

This is an intervention – a message from that space in the margin that is a site of creativity and power24: sick spaces are free spaces.

25

25

1 Yi, Y & Perez, Y. (2021). Passing Through 1. [Digital Photography].

2 Coccia, E. (2018). The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture. Wiley.

3 Hooks, B. (1989). Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness. Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, (36), 15-23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44111660

4 Mitchell, D. (2003). The Right To the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. Guilford Press.

5 Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene. Duke University Press.

6 Pauline Gumbs, A. (2020). Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals. AK Press.

7 Ruth Gilmore Wilson, prison abolitionist and prison scholar; professor of Earth & Environmental Sciences, and American Studies, and the director of the Center for Place, Culture, and Politics quoted in MPD 150 “What are we talking about when we talk about “a police-free future?” https://www.mpd150.com/what-are-we-talking-about-when-we-talk-about-a-police-free-future/

8 Living through a year of a global pandemic marked by fear of the undetectable, the untraceable, the microscopic – a virus – our attention was concerned with what we could not see. It is about the sick space between us, you and me. 6 feet. What lives and dies between those 6 feet? 500,000 COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. The air between us though seemingly empty is charged with an abundance of life, including life form that may be a dangerous threat.

9 Lopez-Pinero, S. (2020). GSD DES3357: Experiments in Public Freedom.

10 Irigaray, L. & Marder, M. (2016). Through Vegetal Being: Two Philosophical Perspectives. Columbia University Press.

11 Original background image for ‘Dirt’ collage sourced from: ScienceTake: The Fungus Highway. (2013). New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/video/science/100000002564178/sciencetake-the-fungus-highway.html.

12 Berthold, D. (2010). Tidy Whiteness: A Genealogy of Race, Purity, and Hygiene. P. 12. Indiana University Press.

13 Berthold, D. (2010). Tidy Whiteness: A Genealogy of Race, Purity, and Hygiene. Indiana University Press.

14 Berthold, D. (2010). Tidy Whiteness: A Genealogy of Race, Purity, and Hygiene. P. 8. Indiana University Press.

15 James, & Boggs, G. (2008). Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century. New York: NYU Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv12pnr39

16 Original background image for ‘Visions’ collage sourced from: Baker, C. (2014). Fungal Freeways. Science Fridays. https://www.sciencefriday.com/videos/fungal-freeways-2/

17 Cache, B. & Davidson, C. (1995). Earth Moves: The Furnishing of Territories. MIT Press.

18 Mitchell, D. (2003). The Right To the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. Guilford Press.

19 Original background image for ‘Visions’ collage sourced from: Baker, C. (2014). Fungal Freeways. Science Fridays. https://www.sciencefriday.com/videos/fungal-freeways-2/

20 Mitchell, D & Van Deusen, R. (2001) Downsview Park: Open Space or Public Space? Springer

21 Further reading on hypnagogia: Haar Horowitz, J. A. (2019). Incubating Dreams: Awakening Creativity. MIT Press. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/578c0c92b3db2b24714cd02d/t/5d4881e66315ae00011e0f55/15650329528 53/Incubating+Dreams+Awakening+Creativity+Adam+Haar+Thesis+8.5.19-compressed.pdf

22 Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene. Duke University Press.

23 Jenkins, Henry. Et al. (2020). Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination : Case Studies of Creative Social Change : Case Studies of Creative Social Change. P.12. New York University Press. ProQuest Ebook Central http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/harvard-ebooks/detail.action?docID=5994221.

24 Hooks, B. (1989). Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness. Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, (36), 15-23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44111660

25 Yi, Y & Perez, Y. (2021). Passing Through 2. [Digital Photography].

Yeh Eun (Yeni) Yi and Yesenia Perez are recent M.Ed ‘21 graduates in Arts in Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.