Morality as a Cure: Catholicism and Working-Class Housing in Early 20th Century Colombia

BY JUAN SEBASTIAN MORENO

“The priests shall teach the ignorant peasant, the informal worker, the unclean poor, the selfish chieftain, that moral and physical perfection will not be reached if cleanliness and order in the rooms and in the people are neglected.”

Miguel Samper, Misery in Bogotá

Colombia’s two main cities, Bogotá and Medellín, radically transformed during the first two decades of the 20th century. The capital, Botogá, expanded from an urban core laid out in colonial times and began to grow in all directions at an unstoppable pace. At the same time, Medellín ceased to be a town of merchants, rapidly transforming into the country’s main industrial hub.

Living conditions for the working poor deteriorated as demographic pressure mounted. While the wealthiest Bogotanos gradually moved north of the city’s center to newly erected, Tudor-style villas, the eastern margin of the city filled with tenements and houses built in a precarious way, where several families of workers lived crammed in tiny rooms. In Medellín there was also a marked housing deficit. For the growth rate recorded in 1918, around 500 new homes would be needed each year to house the new arrivals; the city hardly provided for half.

Public offices and charitable organizations, usually of a religious persuasion, mounted a coordinated effort to provide more and better housing for working families. Hygienic concerns were fundamental for their course of action. At the time, hygienism was a common current of thought in cities throughout the Americas. In its purest version, it established a direct dependence between the moral and physical health of individuals with the environment in which they lived. These ideas came from the theory of miasmas and humors, which dominated medical practice in Europe since at least the fifteenth century. Subscribing to this tradition, some members of Latin America’s urban elites considered hygiene as part of a civilizational project that ought to be carried out to improve the social body.

Accordingly, hygiene-oriented projects in Bogotá and Medellín found an ally in the Catholic Church. Specifically, the Catholic Social Action (in Spanish, Acción Social Católica, ASC), a group of Jesuit priests guided by the Social Doctrine of the Church, was eager to engage directly with the emerging working class and to protect them physically and spiritually.

The material basis of their concerns was legitimate. By 1914, only 4.7% of Bogotá homes had access to water in their households, and only 15% had electricity. At the same time, medical practitioners started to publish their worries about overcrowded dwellings. But the ASC also included a moral crusade that became a strategy to intervene in working-class neighborhoods: the institution focused on building private places, for household and communal dwelling, to closely monitor the workers it took under its charge.

In both cities, hygiene and Catholic doctrine combined to intervene upon the built environment. Local elites and the Church sought to improve the living conditions of the working class by constructing neighborhoods and boarding houses for working women. These improvements also served as a way of controlling the workers’ political activities by isolating them from influences that threatened social hierarchies. Two cases highlight this strategy.

To the south of Bogotá’s historic downtown, the Villa Javier neighborhood represented “the City of God on Earth.” Its construction started in 1913 under the direct tutelage of the Jesuit José María Campoamor. This priest, born in Spain, arrived in Colombia in mid-1910 after working with labor circles – groups of workers organized around Catholic doctrine – in Germany, Belgium and France. For this reason, Campoamor understood the dangers that loomed over the workers and threatened the teachings of the Church: secularism, individualism, and communism. These would be his enemies.

Campoamor realized that the radical influences of anarchism and socialism, deeply rooted in the European working classes, were incipient within Bogotá’s working class. The social illness he combated across the ocean had not yet taken hold. As such, he considered he had the opportunity to create a Catholic community, shielded from revolutionary ideology, that would allow him to improve the material, economic and moral conditions of the lives of the working class. The way to carry out this crusade for their redemption from poverty, destitution, and radical politics was by building a neighborhood for working families.

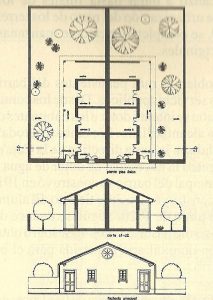

Villa Javier’s physical characteristics were an innovation in working class dwellings for contemporary Colombia. The houses were designed and built to ensure a hygienic, ventilated and illuminated single-family environment. Anton Stoute, a Dutch architect, was in charge of their design, which he divided into three housing typologies according to size. Each house had a small garden that could be cultivated by its residents. In this way, the neighborhood respected peasant traditions of self-subsistence that persisted in some workers by giving them a garden to cultivate. At the same time, Campoamor’s strategy to distribute houses – one per family, with separate rooms – was an attempt to change the workers’ domestic habits of sleeping together in the same room.

Plans, sections, and facades of Villa Javier’s housing typologies. The single- family house represented an innovation for workers’ housing in Colombia. Londoño and Saldarriaga, La cuidad de Dios en Bogotá, 118.

While the neighborhood was built with the family as its basic unit, it also included a series of novel urban facilities: a school, a coliseum, an amphitheater, a chapel and a communal store, among others. The design of the 96 houses that were built combined the hygienic concerns of aeration and lighting, with a large space (almost half of the lot) for orchards or gardens.

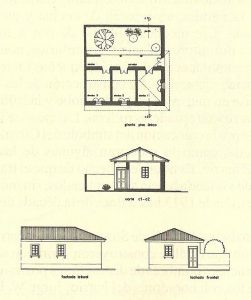

To understand the moral repercussions of this project, it is critical to consider another physical element. Villa Javier was surrounded by a wall that put a barrier between its inhabitants and the rest of the city. Since Father Campoamor was concerned that his experiment would be contaminated by radical ideas, he considered it necessary to educate the families of the neighborhood in Catholic doctrine. But he also took the precaution of physically protecting these workers with an enclosure. In 1913, Villa Javier became Bogotá’s first gated community.

Villa Javier’s urban layout, 1938. The wall is the thick line that surrounds the grid. Londoño and Saldarriaga, La cuidad de Dios en Bogotá, 116.

The wall’s physical and symbolic functions were to delimit the space and to define the extension of the Catholic community that dwelled within. Campoamor imagined this neighborhood as a “space of utopian unity” and, therefore, he erected its border as a safeguard of the sense of community that he fostered. It was a border that simultaneously separated and enforced social cohesion.

Father Campoamor’s neighborhood was not the only way the ASC found to resolve the question of how to guide the way of life of the working class. Medellín’s clergy, which had a close relationship with the region’s merchants and industrialists, were concerned with the arrival of young women to the city who were attracted by the wages offered by the factories of this thriving hub. The episcopate and the factory owners agreed that these women, who in their homes had never been without their parents’ supervision, needed to be watched. For their own good, priests said, these women should have a guide to help them adjust to life in the city and to replace the authority of their parents.

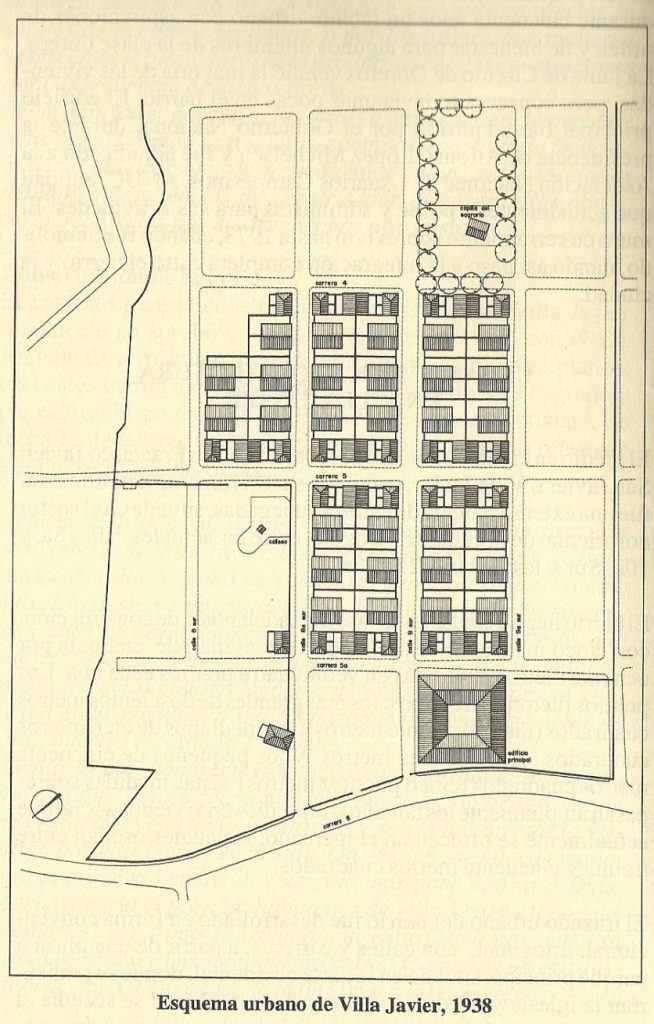

Under this premise, the ASC ran a series of patronatos, or boarding houses. These buildings functioned as both living quarters and training centers, housing young women who were to be employed primarily in Medellín’s nascent textile industry. The first patronato, run by the Society of Jesus, was a public facility opened in 1912. It rapidly became a platform for Catholic labor unions and the political education of the local working class.

But the real impulse to unite labor discipline with religious devotion was felt when Medellín’s industrial elite became involved in the problem. They assumed a paternalistic attitude and promoted a corporate religion, where work ethic always went hand in hand with the observance of Catholic discipline. The best example of this alliance was Fabricato, a family textile business founded in 1923. Its owners preferred to hire women, as they considered them to have a more delicate disposition, ideal for textile work and for operating very expensive equipment imported from the United States.

The patronato for Fabricato’s workers opened ten years after the company started operations. The workers lived together and shared spaces for socializing – a stark contrast to the factory floor, where constant vigilance and massive machinery precluded close contact. The director of the textile company considered that building the boarding house was an act of Catholic virtue, as well as his duty as the overseer of the young women who worked for them. Industrialists and clergymen conflated their preoccupation with hygiene with the morality associated with clean spaces. To buttress their role as surrogate parents of working women, they also enforced a militant adherence to upholding social hierarchies, inside and outside the factory floor.

Fabricato’s Patronato for Working Women (ca. 1940)

In their view, discipline begot virtue. The workers living on the company’s property had to obey clear rules of behavior, intended to train obedient and diligent workers. These norms were enforced by Jesuit fathers and by nuns who resided within the patronato. The priests regulated women’s clothing, controlled their wages, provided religious instruction, and closely monitored their sexual behavior. They watched over relationships with men outside with apprehension, and the pregnancy of a worker meant her immediate dismissal.

This community of pious workers, equally committed to the factory and to Catholic doctrine, was the ASC’s goal. Discipline and moral regulation were part of the hygienist project. The economic and moral salvation of the working class, as Father Campoamor called his crusade, was in practice a strategy to control the public and private behavior of working-class households; a similar result occurred within the framework of industrial paternalism, applied to young women who came from families organized around paternal authority.

The Patronato’s Main Room (ca. 1940)

While in other Latin American countries the main hygiene-oriented interventions were concentrated in the public spaces of the cities, the cases of Bogotá and Medellín demonstrate a greater concern for the domestic and the private. An impoverished and absent state gave way to the Church to exert control of emerging social sectors. In these two Colombian cities, Jesuit priests concerned with the “social question” – that is, the uncertainty generated by cities in upheaval and the gradual appearance of the urban proletariat – worked towards the moral and economic redemption of the workers. Building their dwellings served three purposes: first, they solved immediate material shortages of the workers, since they were hygienic and illuminated houses at affordable prices, which the workers could pay in dues; second, they formed closed communities that kept workers away from influences contrary to Catholic doctrine; and third, they facilitated the vigilance that the priests exercised over their behavior.

However, these places for the working class were more than physical manifestations of hygienist discourse and Catholic doctrine. They also opened up opportunities for industrial laborers to meet and recognize each other, as factories and homes witnessed the emergence of new social sectors that gradually adapted to urban life and factory work. In the first decades of this process, the mediation of the Catholic Church, through the ASC, was fundamental for the creation of practices of discipline, hygiene and work ethics that did not previously exist. The ASC also became a hinge between classes, which interceded on their antagonism and channeled (and largely disarmed) their political power.

The physical and symbolic construction of housing for workers corresponded, in this way, to the transformation of popular sectors. Peasants, artisans and miners became an urban working class. The materiality of place, whether in single-family houses or in conventual boarding houses, set the boundaries for compact communities, defined by the Catholic values that recurrently appeared in the daily lives of the workers.

References

Agostoni, Claudia. Monuments of Progress. Modernization and Public Health in Mexico City, 1876-1910. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2003.

Arango, Luz Gabriela. Mujer, religión e industria, Fabricato 1923-1982. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia-Universidad Externado de Colombia, 1991.

Arias, Ricardo. El episcopado colombiano. Intransigencia y laicidad (1850-2000). Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes-ICANH, 2003.

Botero Herrera, Fernando. Medellín 1890-1950. Historia urbana y juego de intereses. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia, 1996.

Castro, Beatriz. “Los inicios de la asistencia social en Colombia,” CS No. 1, ICESI (2007): 157-188.

Cipolla, Carlo. Contra un enemigo mortal e invisible. Barcelona: Crítica, 1993.

CILEP. “Los orígenes del Primero de Mayo en Colombia y la influencia del anarcosindicalismo,” in Los orígenes libertarios del Primero de Mayo: De Chicago a América Latina (1886-1930), compiled by José Antonio González. Santiago: Quimantú, 2010.

Cueto, Marcos and Steven Palmer. Medicine and Public Health in Latin America: A History. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Folchi, Mauricio. “La higiene, la salubridad pública y el problema de la vivienda popular en Santiago de Chile, 1843-1925,” in Perfiles habitacionales y condiciones ambientales. Historia urbana de Latinoamérica, siglos XVII-XX, coordinated by Rosalva Loreto López. Puebla: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, 2007.

Gaviria Toro, José. Monografía de Medellín, tomo I. Medellín: Imprenta Oficial, 1925.

Gloria, revista bimestral de Fabricato No. 11 (Jan-Feb 1948).

Kothen, Robert. The Priest and the Proletariat. New York: Sheed & Ward, 1948.

Londoño, Rocío and Alberto Saldarriaga. La ciudad de Dios en Bogotá: Barrio Villa Javier. Bogotá: Fundación Social, 1994.

Mejía Pavony, Germán. Los años del cambio: historia urbana de Bogotá 1820-1910. Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana-ICANH, 2000.

Noguera, Carlos. Medicina y política. Discurso médico y prácticas higiénicas durante la primera mitad del siglo XX en Colombia. Medellín: EAFIT, 2003.

Plunz, Richard. A History of Housing in New York City. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Popescu, Gabriel. Bordering and Ordering the Twenty-first Century. UK: Rowman and Littlefield, 2012.

Rajaram, Prem and Carl Grundy-Warr. Borderscapes: Hidden Geographies and Politics at Territory´s Edge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Ramírez Patiño, Sandra Patricia and Karim León Vargas. Del pueblo a la ciudad: migración y cambio social en Medellín y el Valle de Aburrá, 1920-1970. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia, Alcaldía de Medellín, Hombre Nuevo Editores, 2013.

Samper, Miguel. La miseria en Bogotá y otros escritos. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 1969 [1867].

Tavera Zamora, Camilo. Habitaciones obreras en Bogotá. Bogotá: Minerva, 1922.

Vargas, Julián and Fabio Zambrano. “Santa Fe y Bogotá: evolución histórica y servicios públicos (1600-1957),” in Bogotá 450 años: retos y realidades. Bogotá: Foro Nacional por Colombia-IFEA, 1988, 11-93.

Villegas, Benjamín. Bogotá from the Air. Bogotá: Villegas Editores, 1994.

Juan Sebastián Moreno is a second year student of Urban Planning at Columbia GSAPP. His main interest is to study the ramifications of urban informality in Latin America. His work in urban geography and planning policy can be found at juansebastianmoreno.com.