Detroit: Decay, Displacement, and Exploitation

BY JACK SCHULTE

June 30, 2021

On July 18, 2013 the City of Detroit filed for bankruptcy, the largest municipal Chapter 9 filing in American history. Detroit’s bankruptcy marked the culmination of a drawn-out fiscal struggle for the city. After many years of chronic financial and administrative dysfunction, Detroit had become the quintessential example of so-called “urban decay” rampant in American legacy cities. Nearly a decade after the city declared bankruptcy, however, Detroit has entered a so-called “renaissance.” The comeback narrative coalescing around Detroit is matched by real dollars – more than $10 billion has been invested in real estate in Downtown Detroit since 2006 (Jay and Conklin 29). However, the benefits of increased investment and new development have not been equitably distributed. The Black population of Detroit has continued to face discrimination and residential segregation even as the city and its observers promote a narrative of “revitalization.” Excluded from the ostensible benefits of this revitalization, Detroit’s Black population instead has been forced to bear the brunt of its costs.

Detroit’s Neocolonialism

Over the past half-century, Detroit has relentlessly deteriorated. Urban decline impacted cities across America during this time, but Detroit stands out. In 1950, over 1.8 million people lived in Detroit; in 2013, the population was just over 700,000, a loss of well over half of the city’s population (Clement and Kanai 373). Post-apocalyptic images characterizing Detroit’s abandonment and decay proliferated, helping to popularize the nascent genre of “ruin porn.” “Ruin” tours of Detroit became a popular activity for tourists, drawing international travelers. In 2010, two books of photography were published – The Ruins of Detroit and Detroit: Disassembled. These books helped establish a narrative and identity for Detroit in decline, a sick place where residents did not care for or maintain their surroundings. What was always missing in this framework, though, was the systemic racial inequality that framed this decay (Kinney 787). Blind to the racist historical and systemic forces that continue to plague Detroit and drive property abandonment and deterioration, this framework instead presented Detroit as a condemned blank slate, open for “redevelopment.” This neocolonial vision worked to erase the presence of a majority Black population of over 700,000 people.

In her article “‘America’s Great Comeback Story’: The White Possessive in Detroit Tourism,” Rebecca Kinney argues that the discourse around Detroit ignores the realities of racial inequality. She writes, “‘I argue that tourism narratives of ‘exploration’ and ‘discovery’ in which a majority black city is imagined as open, empty, and ready for exploration and settlement by ‘adventurous explorers’ and ‘urban pioneers,’ are a continued project of ‘white possessive logics’” (Kinney 780). Detroit is framed as an unruly, nonwhite urban space that needs to be tamed by white settlers. In “Greening the urban frontier: Race, property and resettlement in Detroit,” Sara Safransky similarly details how historical concepts of white settler society and “green” redevelopment plans are used to reclaim nonwhite land in Detroit. She writes, “[w]here the rural settlers of the 19th century sought to conquer wilderness, “urban pioneers” in the 21st century deploy nature as a tool of economic development in a city with a shrinking population and a large spatial footprint” (237). The arrogance inherent to the position of the “urban pioneer” has worked to make the Black population of Detroit invisible and legitimize a development process that justifies removal and ignores the true causes of urban decline.

The white settler narrative is often linked to private sector financial interests. A poignant example is that of Little Caesars Arena, which opened as the new home of the Detroit Red Wings in 2017. Mike Ilitch, the owner of Little Caesar’s Pizza and the Red Wings, is often praised for his role in the “redevelopment” of Downtown Detroit. However, Ilitch himself was responsible for some of the worst blight in the city. In the Cass Corridor, Ilitch purposefully allowed his property to deteriorate in order to drive down the price of neighboring parcels and purchase them for cheap (Perkins). Ilitch created an artificial dead zone for redevelopment and used this decay as a way to pressure the city and state for public funds. Ultimately, Ilitch was able to receive $324 million worth of public assistance for the arena development. The city also agreed to forego sales taxes on ticket, concession, and merchandise revenue previously collected at Joe Louis Arena – the old home of the Red Wings (Perkins). Kinney writes pointedly, “ the very people most benefiting from the development of the arena were the derelict property owners who drove the property values down and created some of the most blighted areas in our city’s core to garner support for their ‘redevelopment’” (797).

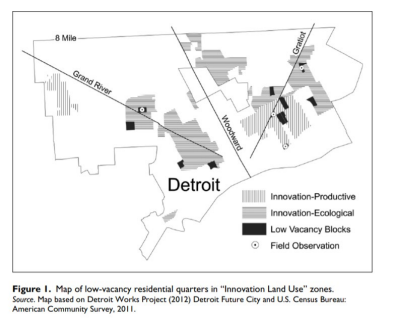

Practices of white neocolonialism in Detroit are evident in the Detroit Future City plan. In 2013, the city government released this 50-year plan through the Detroit Works Project, a public-private partnership. The Detroit Works Project governance consists of an assembly of “public agencies and private actors” (Clement and Kanai 376). The Detroit Future City plan (DFC) advocates a reduction in public services to the city’s highest vacancy and impoverished neighborhoods, shifting these services to actively developing or gentrifying neighborhoods (Jay and Conklin 41). The plan also calls for the repurposing of the high-vacancy neighborhoods into blue and green infrastructure such as urban farms, retention ponds, and greenways. The plan is an apt representation of neocolonialism in Detroit, as the high-vacancy areas deemed “empty” by the plan were home to more than 90,000 people. (Safransky 238). Clement and Kanai’s analysis of the DFC plan concluded that the rezoning strategy would disproportionately impact Detroit’s poorest and most isolated residents. Below, Figure 1 displays the DFC’s rezoning plan. The DFC deemed these zones as “moderately vacant.” Clement and Kanai refute this determination. Instead, they found relatively low vacancy rates and observed “entire blocks of well-maintained, single-family homes with the usual signs of residential life characteristics of mid- to low-density American neighborhoods” (379). Their study details how the presence of the Black population in Detroit is being actively erased by the technocratic imaginary, zoned for removal through “green” restoration. The DFC plan only works to further the racialized spatial injustices experienced by the Black population of the city.

In “The Right to the City,” David Harvey argues that the ability for residents to shape our cities is one of the most fundamental human rights, but one that is often ignored. Harvey’s concepts developed in “The Right to the City” ring true in Detroit. Harvey writes, “A process of displacement and what I call ‘accumulation by dispossession’ also lies at the core of the urban process under capitalism. It is the mirror image of capital absorption through urban redevelopment and is giving rise to all manner of conflicts over the capture of high value land from low income populations that may have lived there for many years” (276). In Detroit, Black residents overlooked and ignored by large-scale planning processes do not have a “right to the city.” Harvey writes, “The right to the city, as it is now constituted, is far too narrowly confined, in most cases in the hands of a small political and economic elite who are in the position to shape the city more and more after their own particular heart’s desire” (277). Private and quasi-private interests hold the right to the city in Detroit. The Black population is forced to suffer and adapt as their city is altered by private interests that treat existing populations as invisible at best and expendable at worst.

“New” Detroit

The infusion of private capital into select areas of Downtown has caused a wave of gentrification in the city and a selective redevelopment aimed towards the new-coming white professionals. This uneven “urban renaissance” has been hailed as a great success by the national media. Between 2010 and 2015, the white population of Detroit increased by 14,000 people, a 25 percent increase. During this same period, Downtown rents have nearly doubled (Jay and Conklin 38). Dan Gilbert, owner of Quicken Loans, has been the main driver of the “revitalization” Downtown. Bedrock, Gilbert’s real estate company, is now Detroit’s largest landlord (Crawford). It’s clear that Detroit is making progress in some selected sections of the city but the question to consider is progress for whom? So far, the main benefactors to the “redevelopment” of Detroit have been private capital and higher-income in-movers.

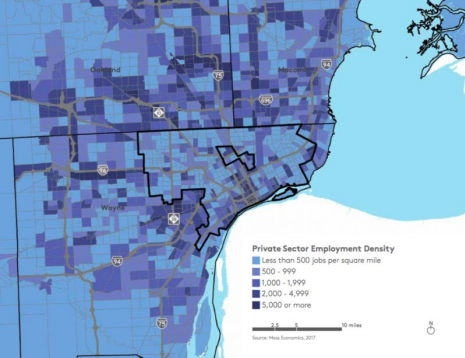

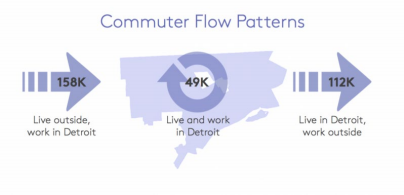

Economic development in select parts of Detroit have increased job growth. But, besides the gentrifying neighborhoods of Midtown and Greater Downtown, the legacy of racialized employment divide has remained strong. In the Figure 1 below, we can see how the employment divide between the suburbs and the city remains strong (Abello). The only difference in recent years is the selected areas of the city where employment has grown. Further, these new employment opportunities, especially the well-paying ones, have been mainly taken by commuters from the suburbs. Native Detroiters mainly leave the city for low-paying jobs in the suburbs. Oscar Abello writes in City Lab, “An estimated 158,000 commuters come into the city for work, 59 percent of whom earn more than $40,000 per year. Meanwhile, an estimated 112,000 Detroiters leave the city for work, 36 percent of whom earn $15,000 a year or less.” This pattern is shown below in Figure 2.

These forces impact not only housing and development, but transit planning as well. The QLine is a recently completed $140 million streetcar system in Downtown Detroit supported by private actors, including Dan Gilbert. Its backers initially promised to pay for the streetcar themselves but later enlisted the US DOT’s support to the tune of $37 million, as well as $10 million from the state of Michigan (Schmitt). There have been many critical reactions to the streetcar mainly due to the fact that the streetcar “does not improve accessibility for transit-dependent populations, who are largely Black Detroit residents with needs for connections to regional jobs and opportunities” (Schmitt). When planning the project, the local government in Detroit was found to subordinate public goals and preferences in favor of private interests (Schmitt). This development fits in with a history of racialized transit policy in Metro Detroit that has consistently hurt the Black population.

Detroit’s suburbs operate their own connected transit service, SMART, while the city’s service, DDOT, operates in isolation. Hostility from the majority-white surrounding suburbs has blocked the integration of these transit systems for decades (Schmitt). This kind of de facto transit segregation is not unique to Detroit. In Atlanta, the largely white suburbs have similarly opposed linking together urban and suburban transit systems.

Conclusion

Detroit’s “redevelopment” has only occurred in select places and has only benefitted select groups. The forces of racial segregation and discrimination in Detroit have changed little since the early 1900s to today. The most significant change is in how this racism has manifested in the city’s recent economic investment. Through the framework of white, settler colonialism Detroit was made available to the benefit of private capital and to the detriment of an existing Black population. The Black community has been largely ignored and restricted from enjoying the benefits of the so-called “urban renaissance” in Detroit. A just future for Detroit can only be achieved if and when power to determine development outcomes is redistributed to existing Black residents of the city.

Jack Schulte is a second year student in the Masters of Urban and Regional Planning program at Cal Poly Pomona. Jack has worked in the sustainable transportation field for several years. He currently works as a Project Manager for Lion Electric, a commercial electric vehicle manufacturer, assisting clients with the adoption of electric vehicles. Jack is interested in environmental equity and hopes to contribute to the creation and expansion of clean and equitable transportation systems in our cities.

Works Cited

Abello, Oscar Perry. “These Detroit Commuting Numbers Show Stark Inequality.” Next City, 22 Aug. 2017, nextcity.org/daily/entry/new-report-detroit-jobs-numbers-pay commute.

Arnstein, Sherry. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” The City Reader, 6th ed., edited by Richard T. LeGates and Frederic Stout, edited by Richard T. LeGates and Frederic Stout. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2016, pp. 63 – 72.

Clement, Daniel, Miguel Kanai, and Richard Grant. “The Detroit Future City: How Pervasive Neoliberal Urbanism Exacerbates Racialized Spatial Injustice.” American Behavioral Scientist 59.3 (2015): 369-85. Web.

Crawford, Amy, and Boston. “Can Detroit’s Suburbs Survive a Downtown Revival?” CityLab, 25 Apr. 2018, www.citylab.com/design/2018/04/can-detroits-suburbs-survive-a downtown-revival/558764/.

Hackney, Suzette, et al. “Is There Room for Black People in the New Detroit?” POLITICO Magazine, 28 Sept. 2014, www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/09/is-there-room-for black-people-in-the-new-detroit-111396?o=2.

Harvey, David. “The Right to the City.” The City Reader, 6th ed., edited by Richard T. LeGates and Frederic Stout, edited by Richard T. LeGates and Frederic Stout. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2016, pp. 63 – 72.

Jay, Mark, and Philip Conklin. “Detroit and the Political Origins of ‘broken Windows’ Policing.” Race & Class 59.2 (2017): 26-48. Web.

Kinney, Rebecca J. “”America’s Great Comeback Story”: The White Possessive in Detroit Tourism.” American Quarterly 70.4 (2018): 777-806. Web.

Perkins, Tom. “How the Ilitches Used ‘Dereliction by Design’ to Get Their New Detroit Arena.” Detroit Metro Times, Detroit Metro Times, 3 Nov. 2019, www.metrotimes.com/news hits/archives/2017/09/12/how-the-ilitches-used-dereliction-by-design-to-get-their-new detroit-arena.

Safransky, Sara. “Greening the Urban Frontier: Race, Property, and Resettlement in Detroit.” Geoforum 56 (2014): 237-48. Web.

Schmitt, Angie, et al. “How Detroit’s Streetcar Overlooked Real Transit Needs to Satisfy a Well Connected Few.” Streetsblog USA, 15 Mar. 2018, usa.streetsblog.org/2018/03/14/how detroits-streetcar-overlooked-real-transit-needs-to-satisfy-a-well-connected-few/.

Schmitt, Angie. “Will Detroit Give the Dream of Better Transit Another Shot in 2018?” Streetsblog USA, 20 Nov. 2017, usa.streetsblog.org/2017/11/20/will-detroit-give-the dream-of-better-transit-another-shot-in-2018/.